The conflict for the Viking Saga, the school newspaper at Northwest High School in Grand Island, Nebraska, started in March when the school administration issued new rules for the journalism class, which produces the content for the newspaper issues. Students were told they had to use their birth names for their byline. Marcus Pennell, a trans Viking Saga reporter, said the administration cited the school board’s ‘controversial issues’ policy, which states, “we do not teach controversial issues, but rather, provide opportunities for their study.”

“We were pretty confused about it. And of course, we didn’t agree on everything,” Pennell said. Students wanted to push back, but they were informed by administration that if they did not comply, blame would fall back on their teacher, so they chose to follow the rule. “We just followed this rule, even though we thought it was stupid,” Pennell added.

Pennell had recently come out and started going by the name Marcus. He published under his chosen name for one month before the new rule was put in place. “It’s not to say that I kind of knew what would happen, but I knew that it would definitely upset a lot of people. It wasn’t fun, and I was pretty upset about it,” he said, “But I keep telling everyone I wish I could say I was more surprised.”

The school’s actions encouraged the newspaper students to dedicate their last issue of the school year, released in June, to LGBTQ+ issues. “We followed the rule, but at the same time, we kind of wanted to, like make a statement or take a stand,” Pennell said, “because we knew they were trying to censor the LGBT students at school and their voices.”

The paper included three stories on the topic: a story on Florida’s ‘Don’t Say Gay Bill,’ the difference of sex and gender, and the history of pride month.

The newspaper was effectively shut down in June–the class that created it wasn’t offered for the fall semester.

Pennell felt the Northwest Public Schools administration and the superintendent retaliated by shutting down the newspaper program.

When the Viking Saga was canceled, it enraged student journalists and free press advocates across the country. “It’s blatant censorship. There’s no other way to look at it,” said Candace Perkins Bowen, director of the Center for Scholastic Journalism at Kent State University.

The paper was published for more than 50 years. The staff of 15 won third place at the Nebraska School Activities Association State Journalism Championship in April 2022.

PROTECTIONS FOR STUDENT JOURNALISTS

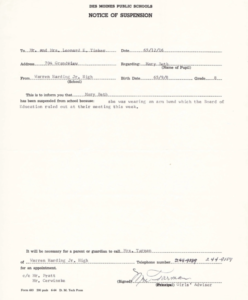

Students’ right to free speech in public schools was established by the Tinker v. Des Moines Supreme Court case, decided in 1969. A group of students in 1965 planned to wear black armbands to their high school to show support for a truce in the Vietnam War. School administrators learned of the plan and made a policy that stated students would be asked to remove the armbands if seen wearing them and a refusal would result in suspension. Christopher Eckhardt, John Tinker and Mary Beth Tinker were three of the five students who were suspended.

“By Christmas time of 1965 I was 13 years old and I was in eighth grade.” Mary Beth Tinker said. “There was a plan that developed at Roosevelt High School to wear black armbands to school to mourn for the dead in Vietnam on both sides of the war. So that’s how we ended up wearing black armbands to school.”

The Tinkers and Eckhardt sued the school district for violating the students’ right to expression. The case made its way to the Supreme Court where it was ruled the armbands represented “pure speech” and students do not lose their First Amendment rights within the school. If the school wanted to suppress speech, they must prove the actions would “materially and substantially interfere” with school procedure.

“I won the case, but I had no idea this case was going to be so important, or that it would be cited thousands of times in other free speech cases for students,” said Tinker. “And then the question for me was, ‘well, now what am I supposed to do with this experience?’” Tinker now speaks with students around the country about how they can take a stand and use their First Amendment rights to advocate “for what would be good for them, to help them thrive, and to reach their potential in this world,” she said.

The freedoms granted by Tinker v. Des Moines are to protect student journalists, including the students at the Viking Saga. The newspaper issue featured other articles outside the three discussing LGBTQ+ topics, including a story on the baseball team, class registration, summer vacation and more. “That’s not really disrupting the school process,” Bowen said. “They came out with this issue that was explaining some of these things [LGBTQ+ topics], fairly factually, and that’s when they said ‘that’s it, no more paper.’”

The local newspaper, The Grand Island Independent, reported the vice president of the school board, Zach Mader, said the board had discussed shutting the student newspaper down in the past if it was deemed “inappropriate.”

Jessica Votipka, the Independent’s education reporter, became interested in the story when she found a handwritten note on her desk that said there was a local, award-winning journalism program whose newspaper was canceled because of a Pride issue. “I told my boss, we need to look into this,” Votipka said.

She found an email sent to the printing facilities on the Grand Island grounds. “The email said basically ‘we won’t be utilizing your printing services anymore because they canceled our school newspaper based on editorial content.’”

After this, Votipka called Michael Hiestand, senior legal counsel of the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), to get in touch with the students at Northwest. “That was tough. It was really tough,” she said about gaining the students’ trust, “But I was hell-bent on getting to know some of these students and getting to know their story.”

The SPLC is a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C. that “promotes, supports and defends the First Amendment and free press rights of student journalists and their advisers” in the fight against censorship.

“Our purpose for existing is to support and defend student journalists and their advisers,” Hiestand said. He primarily answers media law questions that come from students, teachers and newspaper advisors across the country.

The SPLC was contacted in April about school officials at Northwest not permitting students to use their preferred names for their bylines in the Viking Saga. “I provided them with the information, how there’s absolutely no legal requirement that they use the name on their birth certificate,” Heistand said.

“We started getting word, and it was never completely black and white or anything, but we heard that they were going to dismantle the entire journalism program,” Heistand said. “I think the administration felt they had enough of it and decided it was just more trouble than it was worth, so they decided to get rid of it. And then it became a whole different sort of battle.”

Votipka met with the Northwest superintendent, Jeffrey Edwards, after a school board meeting. “He just looked at me and said it was an administrative decision, and just kept repeating that,” Votipka said, “I asked why and he just kept saying it was an administrative decision. And I remember he ended saying something like ‘just report whatever you think is right.’”

Fusion contacted Edwards by email and by phone to ask for an interview or for him to comment on the situation, but he did not respond.

Edwards sent a letter addressed to parents and guardians in Northwest Public Schools that addressed the “speculations” of “what happened with the school newspaper.” He said the journalism program was not being shut down and that there were other journalism-related courses students can take. He also stated the newspaper was “temporarily paused, not canceled,” and that the decision wasn’t made lightly, hastily or due to only one reason. The letter stated the reporter for the Independent [Votipka] “was fully informed of these variables and how the district arrived at its decision but chose to write their interpretation of the situation and disregard the information provided to them.”

Votikpa stands by her reporting. “He’s not saying anything specific. So what am I supposed to respond to? I know I did what I could, I did what I was supposed to do,” she said.

Edwards stated in the letter the paper was not canceled because of the articles about the LGBTQ+ community and added a personal note that he has family members in the LGBTQ+ community. “I would never disrespect them or any of our students that are a part of this community by halting our paper simply because of this subject matter.” He concluded his letter discussing the “inclusiveness” of the student body and how the school is a “safe environment” where students should be who they are “without fear of being treated as anything less than equal.”

Pennell, the Viking Saga writer, said, “It was very much a cop-out kind of letter. I just didn’t find any of those statements to be true.” He wouldn’t describe the student body as inclusive. “I did find communities that supported me,” he said, “but we definitely weren’t celebrated by admin, teachers, or by really anybody other than us.”

In an opinion piece for the Washington Post, Pennell said, “being bullied by peers is one thing. But to be punished by the people who are supposed to be protecting your constitutional right to an education is despicable.” If the administration can bully the LGBT students, he said, “who’s to say our peers can’t. They were never really good at helping us with harassment or anything like that.”

In a recent story by Votipka, it was announced the Viking Saga would return for the spring semester, but in a digital format. This was confirmed in November by Kirsten Gilliland, the former adviser for the paper. This came after demands to reinstate the paper were made by the ACLU of Nebraska.

There is no further update on plans for the paper or how it will function. But Gilliland told Votipka the position of adviser was offered to a different teacher.

In an email, Pennell said,“I believe they changed teachers for the same reasons they shut the paper down—it doesn’t really make sense.” Gilliland, he said, will be replaced by a new teacher who “has zero journalism experience, making this seem like a political move on Northwest’s part in another attempt to silence students whose beliefs don’t align with theirs.”

The decision to bring the paper back initially brought Pennell relief. “I felt really guilty about the closure, so it lifted a lot of that guilt,” he said. “As I learned more information about their plans to return it, the feeling was quickly replaced with the same anger I held for my high school throughout my time there.”

The ACLU is still working to prepare a case to push for the demands included in their initial letter. These demands included not only reinstatement of the Viking Saga, but the “implementation of policies” and “acknowledgement of the missteps that have taken place.”

A group of Northwest graduates also started a non-profit, We Will Press, aimed at supporting student journalists and to keep events like the shutdown of the Viking Saga from happening again.

“I hope that all the attention this story has received hasn’t scared queer students at Northwest into hiding and I also hope that it doesn’t encourage students that hold values of hate to become more vocal through the Saga,” wrote Pennell, “Honestly, we’ll all just have to wait and see.”

HAZELWOOD AND NEW VOICES

In addition to the censorship of student journalists, classroom censorship bills are increasingly growing across the country. Called “educational gag orders” by PEN America, a non-profit that defends free expression, more than 111 bills were introduced in state legislatures this year aimed to limit discussions about race, gender and “controversial topics” in the classroom.

New Voices, a “student-powered nonpartisan grassroots movement of state-based activists” sponsored by the SPLC, aims to protect student journalists and press freedoms by working with state legislatures. Their goal is to counteract the 1988 Supreme Court decision in Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier which affected student press rights.

In the Hazelwood case, the Hazelwood East High School administration censored stories on teen pregnancy and the effects of divorce on children that were published in the school-sponsored newspaper. The ruling, in favor of the administration, was a “dramatic break from nearly two decades of law that had given student journalists extensive First Amendment protections,” according to the SPLC.

The SPLC stated the Hazelwood decision altered the balance of free speech for high school journalists, but that “school officials — no matter what they may believe or claim — do not have an unlimited license to censor; all students retain significant First Amendment protections.”

“Hazelwood was the most harmful court case to students’ free speech rights,” said Tinker, “The decision was a shock to everyone. It was awful.”

Hiestand described the Hazelwood decision as “a roll back on the legal protections of the First Amendment” for students working on school-sponsored newspapers and students engaged in any speech involving some sort of school sponsorship. It also cut back on many of the protections guaranteed by standard set by the Tinker case. “The Supreme Court really gave school officials a much broader authority to censor,” he said. “We tell everybody, they don’t have an unlimited license to censor, but they said the school officials could censor that sort of speech anytime they had a reasonable educational justification for doing so.”

This censorship could include speech being “poorly written,” and “inappropriate,” or if administration decides the speech “is inconsistent with the shared values of a civilized social order.” Heistand described why New Voices laws are so important as they are “turning back the clock so states can never pass a law or enact regulations or rules that provide less protection than that required by the federal First Amendment, but they can always pass a state law that provides more.”

Currently, 16 states have adopted New Voices laws and there are efforts underway in 20 other states. As of now, no laws of this kind have been adopted in Nebraska, despite a bill introduced in January 2021 meant to “provide protection for freedom of speech and freedom of the press for student journalists and to provide protection for student media advisers.” The bill did not make it out of committee in the 2022 legislative session.

Hiestand said a lot of school officials have not caught up with the times. “This probably leads into Nebraska,” he said. “They still think that they do have this unlimited sort of authority to censor, but they learned pretty quickly that times have changed.”

There are currently no New Voices laws in place or in progress in Ohio. “I have my own sort of target states that I really want to get New Voices laws in,” Heistand said, “They make all the difference and Ohio is right there at the top of my list.” He discussed the strong journalism tradition in Ohio, including at Kent State University with the Center for Scholastic Journalism, directed by Bowen. “There’s a reason that the Center for Journalism is there, and it’s cool how valued journalism education is,” he said.

Censorship limits the content available to an audience and to people who may need it. “For me, it’s upsetting thinking about readers not having that kind of content available,” Pennell said “I think growing up, it took me a long time to come out—if I would have read an article like what I had written in the paper, it would have taken less time.” He said the articles also help to humanize LGBTQ+ people to those who haven’t given them much thought. “Queer people will continue to write and continue to publish their work, and this won’t stop them.”

Heistand added that the Viking Saga issue is about the future, “It’s about the kind of the lessons we’re providing to our next generation of citizens about the importance of free press. We hope that’s going to get through at some point but so far, it’s been a tough road.”

Tinker offered advice to all student journalists: “When it comes to your First Amendment rights, it’s like your muscles, if you don’t use them, you could lose them.