Who or what is the root of popular modern language? I’ll give you three guesses. GO. No, it’s not Shakespeare. Or the bible. Definity not Dr. Seuss. It’s, drumroll please… queer people! Yes, much of the buzzwords you learn on the internet and store in your daily vocabulary come from queer, often Black and brown, individuals. Slang, within queer spaces, began as a tool to help those within the community identify each other and protect themselves from a world that did not accept them. Today, thanks to X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and Stan Culture, queer lingo has gone mainstream, for better or for worse. In order to understand how and why this happened, we must take a look back at the journey of queer slang, and in turn, the journey of modern language.

Prohibition, enacted on January 12, 1920, birthed a new type of social gathering at clubs called “speakeasies.” Speakeasies rapidly became a safe haven for gay, queer, and trans people. Within these spaces, queer women began using phrases to distinguish themselves and create subsets within the community. Lavender and Sil were common general terms used for all queer women. Then, terms such as Top Sergeant and Daddy gained popularity in queer circles to differentiate feminine and masculine presenting queer women, similar to how Butch and Femme are used today.

Gradually, different safe spaces for queer people, specifically queer people of color, began to appear in big cities. During the peak of the Harlem Renaissance, The Hamilton Lodge Ball hosted an estimated 8,000 attendees during one of its annual gatherings. This event popularized the term Ball, which came to be known as an event where queer Black and brown people could dress how they wanted, act how they wanted, and be who they wanted without fear of violence or persecution. According to Black Youth Project, “An observer of the Hamilton Lodge Ball explained that the ball brought together effeminate men, sissies, ‘wolves,’ ‘farries, the third sex, ‘ladies of the night,’ and male prostitutes…for a grand jamboree of dancing, love making, display, rivalry, drinking, and advertisement.”” The Hamilton Lodge Ball, and its counterparts in other major cities, hosted some of the first large-scale Drag performances. In these drag shows, queer men and women used heightened forms of femininity and masculinity to critique traditional gender expression. These shows became a staple within the queer community and even attracted spectators from outside the community and around the world.

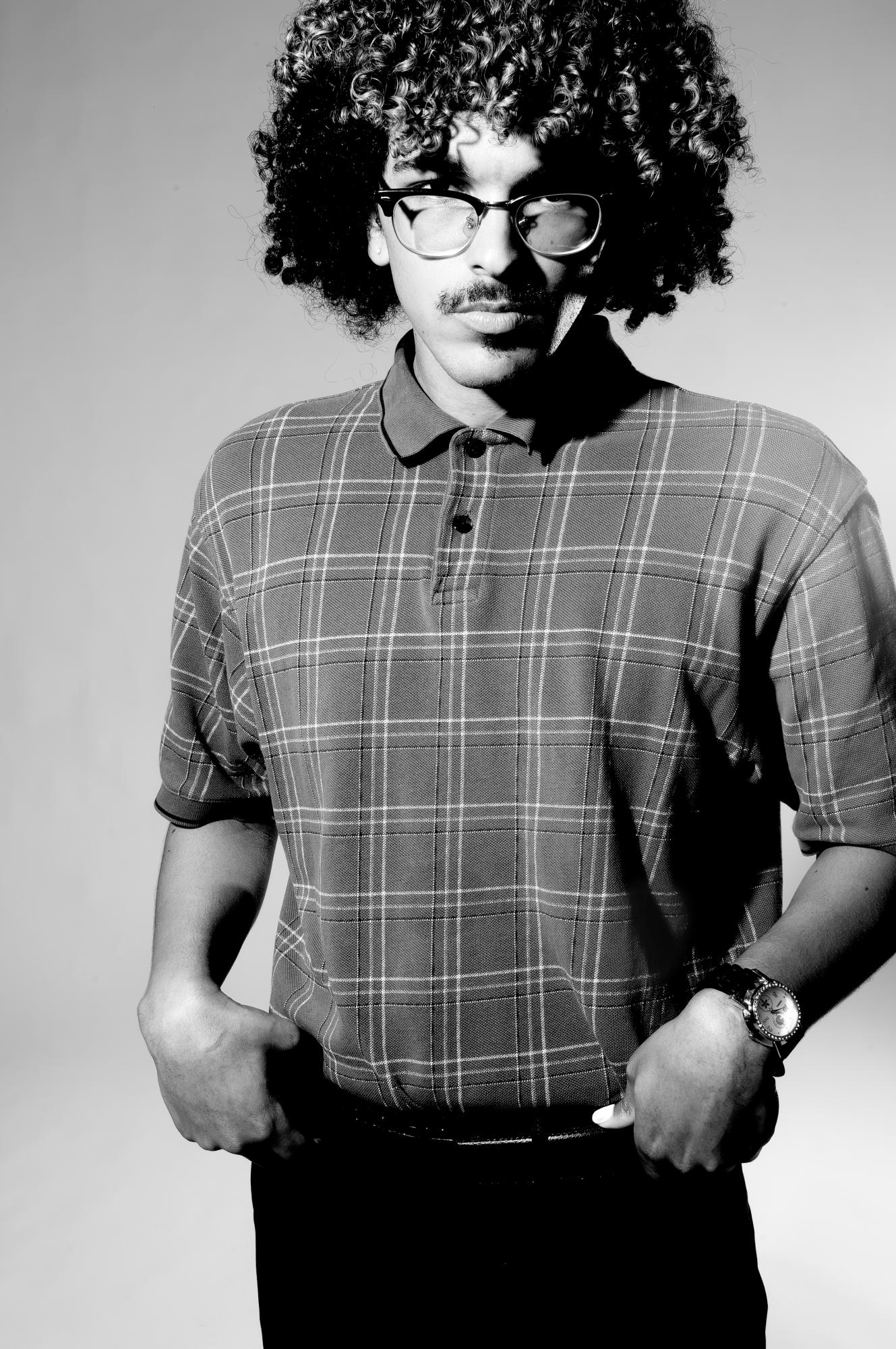

Polari was a dialect used primarily amongst gay men during WWII. It became a secret code of sorts within the community so that gay men could connect with each other outside of the bounds of traditional, heteronormative language. Some of the terms attributed to Polari are still widely used today within and outside queer spaces including: Trade (meaning a ‘straight-presenting’ man who hides his queer identity), and Butch (a queer woman who is masculine-presenting). Another common term during this time period was Friend of Dorothy, also used to describe gay men. The term originated from the belief amongst many that Dorothy’s companions in the Wizard of Oz (the tinman, the scarecrow, and the lion) were written with queer subtext.

Queerness was already frowned upon within society as a ‘moral’ flaw, but the 1950s marked a dangerous period where queer people were targeted and criminalized by the government, who saw their existence as a threat to national security. During what would later be known as the Lavender Scare, thousands of gay men and women were ousted from their jobs and in some cases, arrested, on the basis of their sexuality. Out of fear, queer people across the country were forced to conceal their identities to protect themselves. This was referred to as being Closeted or In the Closet. The act of revealing one’s identity became known as Coming Out. This allegory of being in a dark, isolated place and opening the door to reveal your true self perfectly encapsulated the queer experience. The Lavender Scare, although severely hindering LGBTQ+ progress, also led to a rise in queer organizations that publicly advocated for, and supported queer people.

Amidst the onslaught of persecution against queer people, police conducted routine raids in gay bars around the country. On June 28, 1969, police raided The Stonewall Inn, which led to a riot later known as The Stonewall Riot. The riot became a catalyst for the gay rights movement and in the following year, the first recorded pride parades were held in New York City and Los Angeles. New descriptive terms for queer people, especially queer women, started to gain popularity in these spaces. For Black and brown women, Stud was used to describe a masculine-presenting lesbian woman. Femme was a universal term used to describe traditionally feminine-presenting queer people, including both gay men and women. Queer people in the U.S. now finally had a public space where they could outwardly express their identity.

The 1970s was the era of Camp, a word referring to a type of self expression categorized by its exaggeration and its fusion of pop culture elements. Queer films in the 1970s, such as Rocky Horror Picture Show and Pink Flamingos (which starred Divine, a drag queen), emulated this aesthetic. Both films featured outlandish, often absurd storylines that challenged traditional views on gender, sexuality, and queerness as a whole. To be “camp” meant to completely separate yourself from the confines of heteronormativity. In Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay, Notes on Camp, she wrote, “Camp is a style or mode of personal or creative expression that is absurdly exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” The Camp movement also ushered in a queer sexual revolution, marking a period of public sexual awakening and expression.

The ballroom scene of the 1980s is one of the most influential subcultures in modern slang and language. Phrases such as Serving, Giving, Gagging, Vogueing, and Reading, amongst countless others, were conceptualized in these spaces. The 1990 documentary film, Paris is Burning, chronicled the New York City ballroom scene in the late 80’s. Dorian Corey, a trans woman, said in the film, “In a ballroom, you can be anything you want.” The ballroom featured categories such as “Executive Realness,” “Butch Queen,” and “Luscious Body.” In ballroom competitions, contestants would walk or Vogue (a style of dance within the ballroom named after the poses in Vogue magazine that the movements mimicked) to emulate these various personas and aesthetics. Winners would be given prizes and trophies, which were heavily valued in the community. Ballroom was a space where trans women and gay men of color could escape the relentless hatred and bigotry they faced on a daily basis.

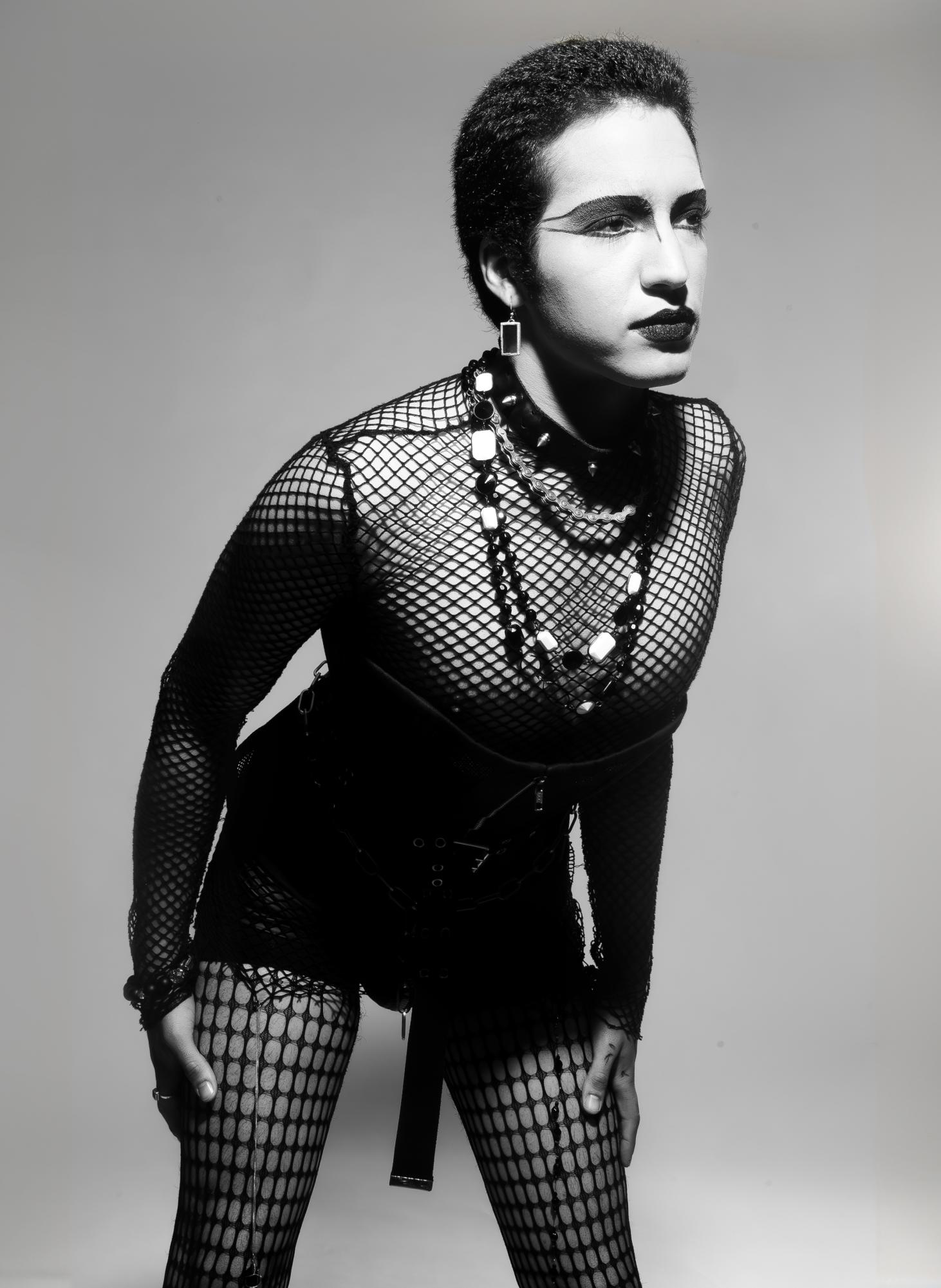

The 1990’s saw the rise of the queer punk movement. Punk represented a direct revolt against authority and government, with punk scenes around the country being involved in political activism for many marginalized groups, including queer people. Punk fashion and music was dark, edgy, and vulgar, being physical representations of punk rebelling against sexual and societal conformity, similar to camp in the 1970’s. Within the punk scene, the word Queer, which had been used as a derogatory term for decades, was reclaimed as an umbrella term encapsulating the LGBTQ+ community. The term Queer became synonymous with pride around one’s identity and culture.

Positive queer representation in the media hit a peak never before seen in the 2000s. Shows such as The L Word, Queer As Folk, Queer Eye, and Rupaul’s Drag Race featured complex, funny, dramatic and beautiful stories of queer people, both fictional and not. In Rupaul’s Drag Race, a reality show competition where drag queens compete to earn the title of “The Next Drag Superstar,” contestants throw shade at each other. The term shade was used prominently in the ballroom scene, meaning to insult someone so subtly and cleverly that they may not even notice that they were insulted. Due to the popularity of queer media like Drag Race and the increasing interest in queer culture by the general public, this phrase became integrated into society outside of queer spaces, and began being used by straight and queer people alike.

The Scissor Sisters, a queer band, released their hit song, “Let’s Have a Kiki” in 2012. To have a Ki or a Kiki is another term that’s origins trace back to the ballroom scene. A Kiki is a party or social gathering amongst friends to laugh, talk, socialize and gossip. To have a Ki describes the act of having one of these events or gatherings. This term, like every term listed, was originally only used within queer communities. “Let’s Have a Kiki” took this phrase, created by Black and brown queer people to describe their intimate social gatherings, and brought it into the mainstream, to be used and appropriated by both non-Black and non-queer people.

How did Cunt go from vile insult to powerful complement? Once again, we have ballroom culture to thank. Outside of queer spaces, Cunt was a word referencing female genitalia and was used for decades as a misogynistic and vulgar insult against women. Within a ballroom, to be Cunt was to be confident, fierce, and fashionable. To Serve Cunt was to represent and emulate these attributes in a manner that demands respect and recognition. Now, Cunt is a common term used among Gen Z on social media and much of its meaning and history has been whitewashed and filtered. This integration of queer slang into the public zeitgeist represents a larger problem with marginalized dialects, including AAVE (African American Vernacular English) being co-opted and appropriated by the very groups that drove oppressed people to create them in the first place.

When it comes to modern language and slang, we have queer people, especially queer people of color, to thank. Slang within the queer community began as a form of protection amid violence and persecution. Now, with increasing representation in public spaces, queer language has been integrated into and appropriated by the general public with many neglecting to understand the deep history and culture of the words that they use everyday. With this being said, if a queer, Black, or marginalized individual implores you not to use a phrase or word that was created within the confines of their community, listen and respect their wishes. Millions of people within the community fought for the basic right to exist and the creation of their own language was integral to their struggle and their eventual liberation.